New developments in transportation

The construction of the

Cumberland Road from 1811 to 1839 and the changes in travel it brought to its

users would give birth to a new idea of what transportation needed to become. Changes

in transportation between 1820 and 1840 stimulated Western expansion and

prompted an influx in work opportunity. Shifts in American culture in this time

period can be greatly attributed to new methods of transportation such as the

construction of further reaching canals, the use of steamboats, and beginnings

of the railway system. With new forms of travel and trade, people began to form

opinions on what the "best" method actually was. Since the need for

expedited travel and trade increased with the Embargo Act of 1807, American

interests in further development of new transportation methods peaked between

1820 and 1840.

Although the most notable roads and canals existed after 1820, the most prominent method of travel and trade up until then was the turnpike (toll road) system which had originated in the 1780's. "The United States only had about 100 miles of canals in operation in 1816, and most of them were only several miles in length" (Wyatt III, 91). The main discussion for governments when it came to making improvements was not based on the topic of what new developments in transportation would bring, but rather how much they would cost. The time and money it took for roads to be constructed in comparison to canals was a difference of seven to eight years and between $3000 to $15,000 dollars, per mile. However private investors backed by state support took their chances and the first portion of the Cumberland Road was opened for use in 1818.

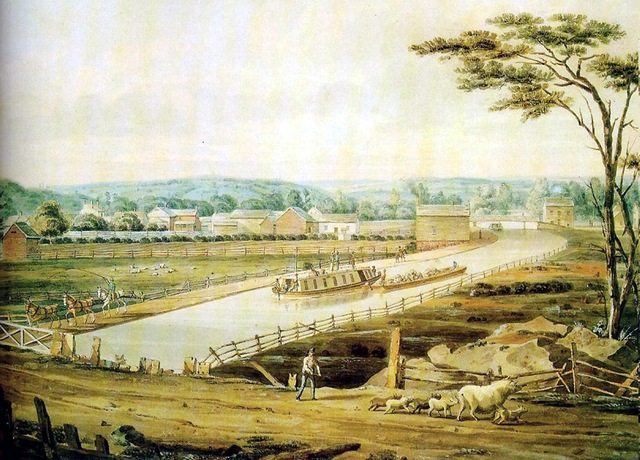

"Work on the Erie canal ended officially on November 4, 1825," and a year later 99 other canal projects would already be underway all over the U.S. (Wyatt III, 92). It is clear that with use of these new innovations in transportation, people and goods alike were moving as rapidly as the newly increased flow of income. "By 1840 the mileage of canals in operation in the United Sates measured more than the distance from the Atlantic to Pacific Oceans:" which was a feat that had come about from the development of a new culture centered on expediting travel and trade (Wyatt III, 92). “Between 1787 and 1860,” state governments spent about ten times more than federal governments, which were already spending $60 million dollars on improvements for these new methods of transport (Foner, 322). With over 3,000 miles of canals by 1837, the cost of transportation for merchants and commoners had reached a new all-time low.

By 1831 there were more than 200 steamboats being used across the Great Lakes, the Mississippi River, and the Atlantic Ocean for travel and trade. This method of transportation was the first to allow upstream, or against current navigation. However, this advancement in technology wasn't a truly notable one until 1807, when Robert Fulton sailed from The Hudson River to Albany New York. With the ability to travel upstream, farmers and merchants were able to spread their market of crops up and down the Mississippi River with much more ease of access than ever before. The impact in culture this made was tremendous in the sense that less money was being spent on getting from place to place, meaning more room for economic growth for any merchant moving goods from place to place. With more goods to be sold in various places, there was more room for population increases and spreads across the United States.

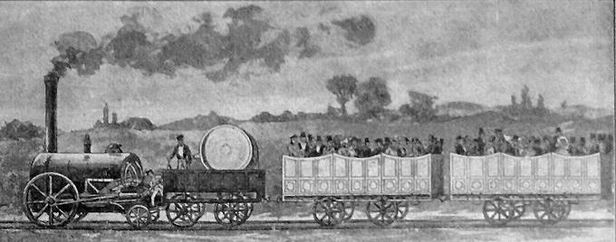

The water canals along which these steamboats traveled served as a "fertilizer," explained novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne; "it causes towns with their masses of brick and stone, their churches and theaters, their business...to spring up" (Foner, 322). One could argue that the development of the railway system worked hand in hand with that of the steamboat. With the need for coal to be used for fuel, as well as the manufacture of iron to build steamboats, locomotives, and rails; new areas were explored and settled along the interior of the U.S. in order to attain the resources needed to develop these innovations. This created an influx in workforce and a demand for population increases in various areas of America. With the full blown spread of already various cultures from the East to the West, new innovations in transportation during the first Industrial Revolution brought together cultures that had grown separately, creating the base for cultural differentiation that we see across present day America.

Although the most notable roads and canals existed after 1820, the most prominent method of travel and trade up until then was the turnpike (toll road) system which had originated in the 1780's. "The United States only had about 100 miles of canals in operation in 1816, and most of them were only several miles in length" (Wyatt III, 91). The main discussion for governments when it came to making improvements was not based on the topic of what new developments in transportation would bring, but rather how much they would cost. The time and money it took for roads to be constructed in comparison to canals was a difference of seven to eight years and between $3000 to $15,000 dollars, per mile. However private investors backed by state support took their chances and the first portion of the Cumberland Road was opened for use in 1818.

"Work on the Erie canal ended officially on November 4, 1825," and a year later 99 other canal projects would already be underway all over the U.S. (Wyatt III, 92). It is clear that with use of these new innovations in transportation, people and goods alike were moving as rapidly as the newly increased flow of income. "By 1840 the mileage of canals in operation in the United Sates measured more than the distance from the Atlantic to Pacific Oceans:" which was a feat that had come about from the development of a new culture centered on expediting travel and trade (Wyatt III, 92). “Between 1787 and 1860,” state governments spent about ten times more than federal governments, which were already spending $60 million dollars on improvements for these new methods of transport (Foner, 322). With over 3,000 miles of canals by 1837, the cost of transportation for merchants and commoners had reached a new all-time low.

By 1831 there were more than 200 steamboats being used across the Great Lakes, the Mississippi River, and the Atlantic Ocean for travel and trade. This method of transportation was the first to allow upstream, or against current navigation. However, this advancement in technology wasn't a truly notable one until 1807, when Robert Fulton sailed from The Hudson River to Albany New York. With the ability to travel upstream, farmers and merchants were able to spread their market of crops up and down the Mississippi River with much more ease of access than ever before. The impact in culture this made was tremendous in the sense that less money was being spent on getting from place to place, meaning more room for economic growth for any merchant moving goods from place to place. With more goods to be sold in various places, there was more room for population increases and spreads across the United States.

The water canals along which these steamboats traveled served as a "fertilizer," explained novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne; "it causes towns with their masses of brick and stone, their churches and theaters, their business...to spring up" (Foner, 322). One could argue that the development of the railway system worked hand in hand with that of the steamboat. With the need for coal to be used for fuel, as well as the manufacture of iron to build steamboats, locomotives, and rails; new areas were explored and settled along the interior of the U.S. in order to attain the resources needed to develop these innovations. This created an influx in workforce and a demand for population increases in various areas of America. With the full blown spread of already various cultures from the East to the West, new innovations in transportation during the first Industrial Revolution brought together cultures that had grown separately, creating the base for cultural differentiation that we see across present day America.

Sources

Foner, Eric. "Give Me Liberty! An American History." Vol. 1. 4th ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2005. 318-353. Print.

John Scott Elder, "The First Steamboat on White River: From the Journal of an Old Pilot," ed. Emma Carleton, Indiana Magazine of History 2, no. 2 (June 1907): 95-96.

Olson, James Stuart. Encyclopedia of the Industrial Revolution in America. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2002. Print.

Wyatt, Lee T. The Industrial Revolution. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2009. Print. Greenwood Guides to Historic Events, 1500-1900 .

Image 1 "Erie Canal": http://www.eriecanal.org/general-1.html

Image 2 "Passenger Railway": http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:First_passenger_railway_1830.jpg

John Scott Elder, "The First Steamboat on White River: From the Journal of an Old Pilot," ed. Emma Carleton, Indiana Magazine of History 2, no. 2 (June 1907): 95-96.

Olson, James Stuart. Encyclopedia of the Industrial Revolution in America. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2002. Print.

Wyatt, Lee T. The Industrial Revolution. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2009. Print. Greenwood Guides to Historic Events, 1500-1900 .

Image 1 "Erie Canal": http://www.eriecanal.org/general-1.html

Image 2 "Passenger Railway": http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:First_passenger_railway_1830.jpg